Tsar reimagines the reign of Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia. Players occupy the center of his regime, advising and influencing him while competing to advance their own factional goals. The game captures the interplay of public opinion, war, diplomacy, culture, internal order, the economy, and the personal traits of Tsarist leaders and the imperial family. Through this simulation, Tsar explores the inner workings of autocratic regimes, with a realistic portrayal of official corruption, the cult of personality surrounding the Tsar, the violence of oppression and resistance, and the conditions that led to revolution.

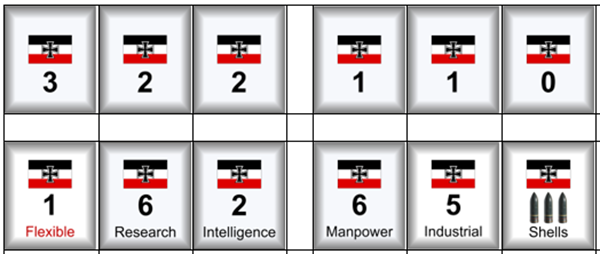

Each player controls a different Faction within the Tsarist regime, and the players get their decision-making capacity through the placement of their Faction’s Characters. Characters can control offices in the government (for example, the Minister of Industry), and they can earn Influence cubes used to persuade the Tsar: these cubes can function as action points in some instances, as a bidding mechanism in joint decisions, and as a way of triggering scoring. But it’s not enough to persuade the Tsar—players also need resources and need to meet certain conditions on the game board to execute their choices. For example, if you want to use the regime’s troops to suppress a labor strike, you’ll need to use transport and supplies, and the army’s morale has to be at a certain level.

So there’s a lot of resource management in the game and a lot of different factors tracked by the game board. You need to make projections about how much money, transport, food, and industrial output the regime needs, and that in turn depends on a bunch of other factors like popular support, trade levels, industrialization, and so on. In multiplayer mode, all these resources are shared and all the conditions on the board apply to all players. This is part of the game’s semi-cooperative nature: you’re all in this government together, although your objectives are somewhat different.

There’s also a worker placement mechanic in the game for various units, most significantly for the Tsar himself. The Tsar isn’t a playable character, but he’s very much at the center of the game. You have a wooden token representing the Tsar and various places on the game board where he can go. This token has two orientations so that it can also track his mood, which affects the things he’ll do or not do. He starts each round in Tsarskoye Selo and you can move him to another location once per round. For instance, you can send him to Moscow to bless the troops and improve morale, or put him on the imperial train to tour the empire and shore up popular support, or send him on a state visit to improve foreign relations. To refresh his mood, you can send him on a season-specific vacation: the Livadia Palace in the Crimea in the spring, the imperial yacht in the summer, and his hunting lodge in the fall (in the winter, he can remain near the capital to host a ball). His movements have a political angle, too: for certain goals, he needs to remain near the capital; alternatively, you can hide some problems from him by getting him away from the capital. In his actions and reactions, the personality of Nicholas II will show itself: he’s indecisive, a bit shallow, often frustrated, distracted by his family, and not particularly competent, but in theory he has a lot of power.

In addition to sharing resources, players in a multiplayer game share the cards. There’s just one hand of playable cards for all the players and even the Character cards are usable by all the players—you can, for instance, place another player’s Character in a particular office. The game uses a couple of different decks, most of which are randomly shuffled: an “Era” deck with a mix of “All Era” and Era-specific events, an “Unrest” deck that simulates resistance, and a “Famine” deck that simulates food shortages.

But for this discussion, I’d like to focus on the “Coded” deck, which is a more unusual feature of the game. This deck has numbered cards that are seeded in response to specific decisions, dates, or conditions. This deck functions together with a series of card slots on the game board that control the timing of the cards. The game is divided into seasonal quarters, each of which is played as one round in the game. So you have a “Q+1” slot holding cards that will be played next quarter, a “Q+2” slot for cards that will be played the quarter after that, etc. Coded Cards in these slots are always viewable, so you can see certain predictable events that are coming up and you can prepare for them. For example, if you take out a loan from France, you’ll seed a Coded Card in the “Q+4” slot that requires an interest payment one year from now, and until you pay off that loan, you’ll reseed the card in the Q+4 slot every time you play it: so you have annual interest payments. Some of the Tsar’s movements that I described above are controlled by Coded Cards that come up at regular intervals, tied to the seasons. So every summer, the Coded Card for the imperial yacht becomes available. You have another Coded Card for the Tsar’s state visits, and after you play it you’ll reseed it in the Q+2 or Q+3 slot. Other Coded Cards are one-time historical events—for instance, the Tsar’s son will be born in the summer of 1904, and Austria-Hungary will declare war on Serbia in 1914. Some Coded Cards are seeded in response to certain conditions: if the navy’s morale falls to zero, the game board will reveal a Card Code for a naval mutiny; if relations with the U.K. fall to zero, the board will reveal a Card Code for a war against the British Empire. The Coded Cards also allow players to create chains of events: if you begin construction on a stage of the Trans-Siberian Railway, you’ll have an opportunity to complete that stage two rounds later; if you send the Tsar on a state visit to France in Era III, you’ll draw a Coded Card that lets you renew the Franco-Russian alliance. So this Coded Card system allows for a more realistic simulation than you would get through shuffled cards alone, and it gives the players more information that they can use to plan their strategies.

Richard Charques, The Twilight of Imperial Russia (1958).

Marc Ferro, Nicholas II: The Last of the Tsars (1990).

John Hanbury-Williams, The Emperor Nicholas II as I Knew Him (1922).

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, The Last Tsar: The Abdication of Nicholas II and the Fall of the Romanovs (2024).

Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador’s Memoirs (1923).

John Curtis Perry & Constantine Pleshakov, The Flight of the Romanovs: A Family Saga (1999).

- Robert D. Warth, Nicholas II: The Life and Reign of Russia’s Last Monarch (1997).

Knight Without Armour (United Artists 1937).

The Last Command (Paramount Pictures 1928).

- Nicholas and Alexandra (Columbia Pictures 1971).